Established in 1909

Steeped in rich history and cultural significance, Nippon Kan Theatre stands as a testament to the vibrant heritage of Seattle’s International District. Built in 1909, the building was created to serve community, culture, and gathering.

Had it been completed on time, the building would have also served as an information center and rest stop for Japanese tourists visiting the city for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

Nippon Kan commissioned architects Thompson & Thompson to design a four story building, including a basement. The ground floor featured retail spaces facing Washington Street, while the second floor housed the theatre and additional retail facing Maynard Avenue, with hotel rooms located above. The same architectural firm was responsible for many buildings throughout the International District.

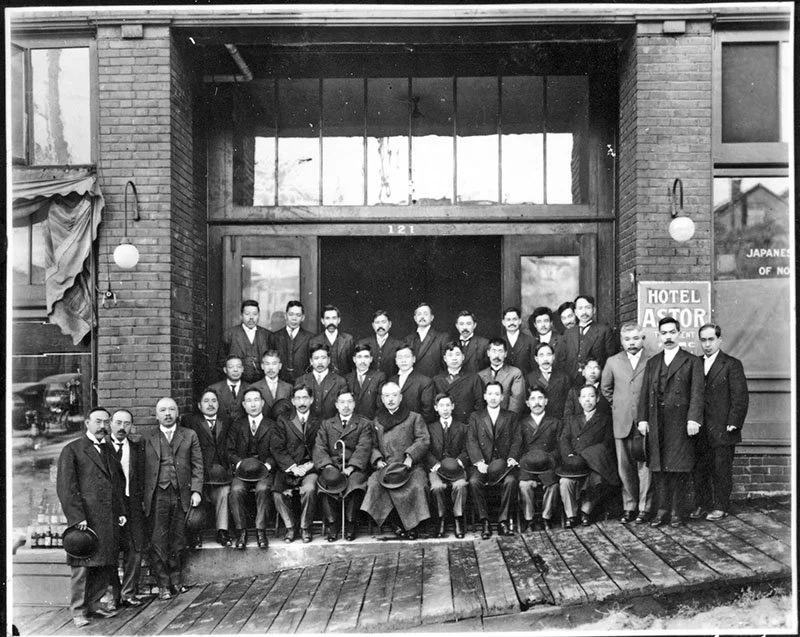

By the time construction began on the $80,000 project in 1909, the building had come under the leadership of the Japanese Association of Washington, with Charles T. Takahashi serving as president, H.H. Okuda as vice president, and S. Hayashi as treasurer. The building was officially dedicated in January 1910. Nippon Kan originally referred to both the theatre and the hotel within the building, though by 1912 the hotel was renamed the Astor, a name it retained until the late 1960s.

For many years, Nippon Kan Theatre was active several nights a week, hosting actors and musicians from Japan, film screenings, concerts, judo and kendo competitions, and community gatherings. Seattle’s only Japanese language daily newspaper, The Asahi, was also published within the building.

In 1942, the theatre was boarded up during the forced incarceration of Japanese Americans. Decades later, in 1981, the space reopened through the restoration efforts of Seattle architect Edward M. Burke and his wife, Betty. Today, the building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

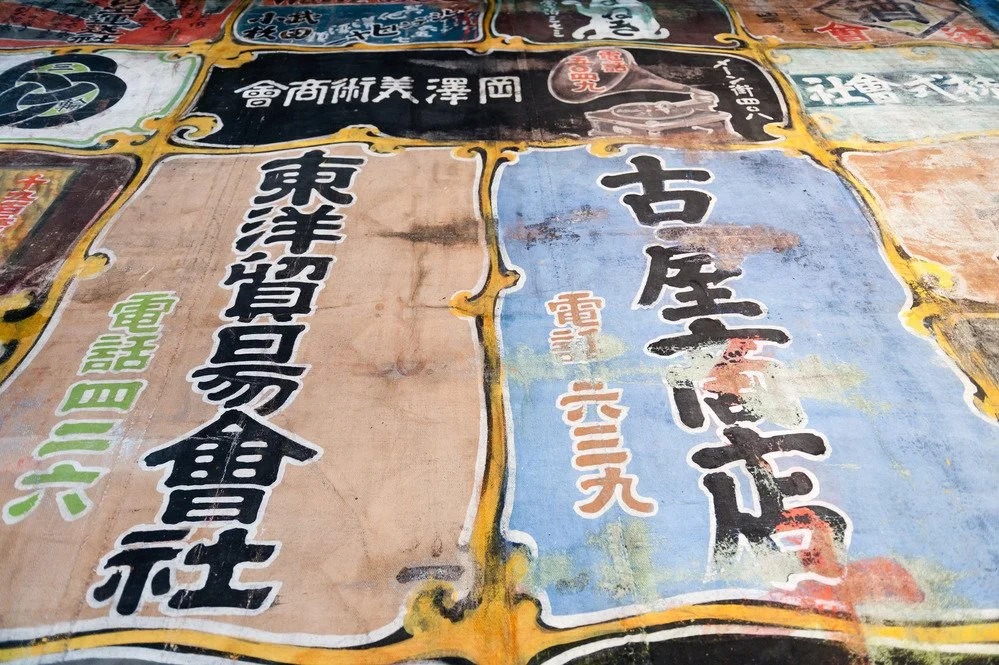

A replica of the original stage curtain hangs on the wall alongside historic photographs from the theatre’s early years. The original closure of Nippon Kan has been attributed to the declining Japanese American population in Seattle during the mid twentieth century.

The theatre’s original stage curtain, used between 1909 and 1915, still survives today. It now hangs at the Tateuchi Story Theatre at the nearby Wing Luke Museum, where it continues to serve a similar purpose. Covered in early advertisements, the curtain was rediscovered in the 1970s. Due to the presence of asbestos in the material, it has since been safely preserved and encased in resin.